Life in Rural Germany – Changing Times

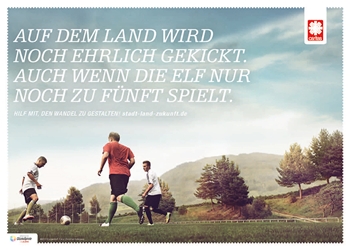

"Honest football is being played in the country side even if the team only consists of 5 players." The Caritas campaign 2015 deals with the changes in rural areas.Deutscher Caritasverband/Christian Schoppe

"Honest football is being played in the country side even if the team only consists of 5 players." The Caritas campaign 2015 deals with the changes in rural areas.Deutscher Caritasverband/Christian Schoppe

In Dennin in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Henning Schroll is buying out half the village, reconstructing the houses and still not increasing rents. In his study the 51-year-old explains why he does this: "When the baby boom generation retires in ten, fifteen years, half of my employees will be among them." To make sure that enough workers will want to move to Dennin by then, he has to invest especially into the lower village where many residents are unemployed. They cannot maintain the old little clinker houses. In order to keep up the appearance of the town Henning Schroll invests. "I cannot and don´t want to raise the rent. Where should the present leasers take the money from?"

The lower town of Dennin actually has the beauty of a romantic postcard: The church with the wooden tower is standing on a little hill among many oak trees. Reddish brown clinker houses are surrounded by rape fields. The image reminds you of a time long ago: a time without advertising, without traffic signs, without cars. But tourism is booming somewhere else, at the Baltic Sea, for instance, at the lake district.

The German population is shrinking

Unemployment and decay of the infrastructure are very distinct in Dennin. Yet these are problems that all of the rural German communities are facing: rural migration, structural changes and above all the demographic development. Germany’s population is getting older. Since 1972 more people have died than have been borne. According to Federal Statistical Office Germany’s population will have shrunk by 12 million people by 2050. At the same time more and more people are moving into the towns as new jobs in our knowledge society become available mostly in urban regions and big cities. Farming has long lost its importance as an employer.

Each region is faced with different problems and underlying conditions. That makes it difficult to talk of "the countryside". Nevertheless this problem concerns many people in Germany: 54 percent of the population lives in villages, communities and small towns. At the same time about 90 percent of Germany’s surface area is considered "rural space".

The demographic changes have a dramatic impact on areas that are already structurally weak: As the baby boom generation of the 50s and 60s ages it leaves a gap that can hardly be filled anymore, especially in East Germany. Until 2050 around 200,000 less people are said to be living in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern than today. With an average of 70 habitants per square kilometer it is already currently the most sparsely populated German State.

The Young are moving West

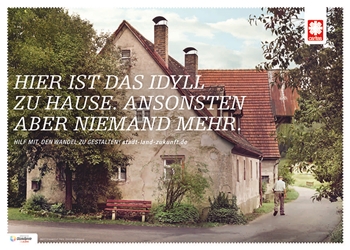

"Here the idyll lives. But apart from that no one else."Deutscher Caritasverband/Christian Schoppe

"Here the idyll lives. But apart from that no one else."Deutscher Caritasverband/Christian Schoppe

With life getting tougher and tougher and no jobs on offer, many young people don´t feel like staying. Since 1990 about 2 million mostly young and well educated people have left East Germany in the direction of West Germany. Brandenburg has the lowest birth rate. In the last ten years every third school has been closed down and the number of students has halved.

In Dennin there is no more social infrastructure. There is no grocery store, no club, not even a doctor or nursing service. There are no busses running between the village and nearby Anklam which is 3km away. People in this village are just existing - no longer living. Yet things have not always been like this. For hundreds of years a village like Dennin used to be the home of farmers and agricultural workers. Fertile soil has made the land an ideal for agriculture then and now - and provided work and food.

The 20 helpers of Henning Schroll are living right next to their workplace in the upper village. The lower village is inhabited by those who don´t have any work, because the farmer needs less and less field workers due to modern harvesting machines. While he grows grain, rape and sugar, his helpers mainly have to take care of the 750 pigs and the 200 milk cows. "If it was not for the animals, I would only need support during harvesting season", explains Schroll.

In contrast to the old states of Germany no strong economy developed after 1990, thus Mecklenburg-Vorpommern has a rate of unemployment of 10.5 percent (the third highest rate of unemployment in Germany after Berlin and Bremen). The region that Dennin is located in has an even higher rate: 12.7 percent.

Click here, to read more about german countryside.

A negative outlook creates negative morale

“In the olden days, during the period of the GDR life in Dennin was wonderful“, says Gudrun Koepp.Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

“In the olden days, during the period of the GDR life in Dennin was wonderful“, says Gudrun Koepp.Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

In one of the clink houses Gudrun Koepp, one of Schroll’s tenants, sits at the table. As most of their neighbours she and her husband are unemployed. One of their daughters moved away to the Westerwald. She talks about the vicious circle that has reigned here since the reunion: Lack of prospects and poverty have poisoned life in the village throughout the years. “When neighbours start to steal wood from one another dispute is not uncommon“, says the 53-year-old.

Since Gudrun Koepp lost her job, she has been nursing her mentally and physically disabled adopted daughter – and working voluntarily at Caritas. After more and more neighbours moved to the nearby town of Anklam she has become the good soul of the lower town. She is helping the “bachelors“, older single men. Some have alcohol problems. If needed she also drives to town to go shopping for her neighbours. With her voluntary work at Caritas Anklam she wants to help neighbours in the lower town as well. If someone needs support she calls somebody from the “Carimobil“ who then comes with a van to Dennin and helps with visits of public authorities, for example.

Despite all the negative prospects life in the countryside also has positive aspects for Koepp. She grew up here with six siblings. After getting married she briefly lived in a town, but after a few days she missed the quietness and nature. “In the olden days, during the period of the GDR life in Dennin was wonderful“, she recalls. “There was one store to go shopping and everyone had a job. Often neighbours would sit outside together and chat“, she reminisces.

When there is no employment, no medical care and nowhere to shop, the countryside will only prosper when individuals get active. The communities have not been able to do all the work. They cannot force the moving in of doctors. And when funds are low the first investment that stops is in the areas of sports and culture. Water supply, effluent, garbage collection and street maintenance are costly key areas that need to be covered first.

Thus entrepreneurs like Henning Schroll have to create a village that makes people want to stay. Part of which also means that he is giving life to the village: He has set up a parish hall at his farm – which is used only by the people of the upper village. The lack of prospects makes the relationship between the villagers. “I am trying to create a positive atmosphere by greeting everyone in the village. You have to keep in touch“, says Schroll.

In Kinzigtal life is good

When Justine had a heart attack a helicopter had to get her as the entire area was inaccessible due to snow during the winter.Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

When Justine had a heart attack a helicopter had to get her as the entire area was inaccessible due to snow during the winter.Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

On the opposite side of Germany, a little more than 700 kilometers away, is Kinzigtal in the southwest. The region of Ortenau where Kinzigtal is located has 229 inhabitants per square meter and is among the densely populated region of Baden-Württemberg, a “rural area“. This is also a picture-postcard village: Alongside the Black Forest drawn-out villages with colourful houses, many of them half-timber with gardens.

Although this region is not part of the outskirts of a town it does well commercially. There is virtually no unemployment which is reflected in the healthy state of the communities’ finances. You will find here medium-sized enterprises of the metal working industry or automotive suppliers like in the rest of the country. The gross domestic product per capita of Baden-Württemberg of 37.400 Euros in 2013 was the third highest of all German states.

But this region is also undergoing demographic changes. In Oberharmersbach with 2500 inhabitants 81-year-old Fridolin Huber lives with his wife Justine. Their old farmhouse is situated deep in the Black Forest. After leaving the village you still have to drive around ten minutes until you get to their farm on the elevated plain. When Justine had a heart attack, ten years ago, a helicopter had to get her as the entire area was inaccessible due to snow during the winter. Today she needs her husband´s help for walking.

Someone from the staff of the Caritas station comes visits her twice a week for three quarters of an hour at a time. As everywhere else in the countryside the caretakers have to put up with driving long distances. From their workplace they need about 30 minutes to get to the Huber farm.

It will become more and more a challenge in future: In Baden-Württemberg the number of people in need of care will also increase. According to a prognosis of the census bureau every third German person will be older than 65 by 2060; many will be living in the country. The young, however, move to where the jobs and the future are: into the towns.

The Hubers are lucky as their son Bernd is still living in the house. They don´t want to give up the big forester´s house with views on the valley of the Black Forest. Fridolin Huber was born here. His life is closely connected to the woods right in front of the house. For generations the Huber family has worked as forest officials, which is also the occupation of their son Bernd. When Fridolin Huber started work in the 1950ies, there used to be 30 forest officials. Now there are only 7 left. The changes in agriculture and forestry are evident everywhere – including the Kinzigtal.

Fridolin Huber is aware that his hometown Oberharmersbach is changing. There used to be six stores, now there are only two left. The doctor has left. He visits the village just twice a week for two hours. There used to be four schools of which two are now closed. Nevertheless life in the village is flourishing. There are clubs for sports, music, singing and carnival activities, although it is getting increasingly difficult to find volunteers for them. Fridolin Huber was active as a fire fighter for 60 years.

While the cities will continue to grow, the Ortenaukreis will also lose an average of 0.5 percent of its inhabitants until 2030. Compared to rural migration in the east this does not have to be cause for concern. If the communities don´t want to shrink, those responsible need to see above all that families with children are staying. One single community cannot achieve much, but together they can.

A school bus drives to speech therapy

As the working structure has changed so have the living conditions in the countryside. Especially single parents are under pressure to combine work and family life. Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

As the working structure has changed so have the living conditions in the countryside. Especially single parents are under pressure to combine work and family life. Philipp Rudolf/ DCV

Christine Giesler is 32 years old and single mum to her two daughters Loreen and Celine. They live in Mühlenbach in Kinzigtal, about 20 Kilometers from the Huber family. The village has 1600 inhabitants. Seven-year-old daughter Celine goes to speech therapy. Every morning she gets picked up and at midday the bus brings her home.

Ten-year-old Loreen goes to primary school in the village. Next year she will go to all-day-school in Haslach. She will then also take the school bus. Schools in Kinzigtal are eager to offer all day care which benefits working and single parents. As the working structure has changed so have the living conditions in the countryside. Especially single parents are under pressure to combine work and family life. Christine Giesler works as a nursery-school teacher in Nordrach, 25 kilometers away from her house. As well as the Huber family and the Koepp family she is dependent on the car. “If I had to take the bus, I would have to change three times and it would take me 2 hours,“ she explains.

Even if commuting is sometimes stressful she would not want to leave the countryside.“The kids can play here by themselves in front of the house,“ she says. In addition you can rent or buy accommodation at reasonable prices. For 100 square meters Christine Gieler pays 500 Euros, including water and heating charges. “In the small town of Haslach I would have to pay 200 Euros more.“ Another advantage of living in the country are the clubs of the village. Everbody finds something that suits him/her. She is involved in the local costume group of Mühlenbach.

She stays in touch with friends who live further away via the internet. In the countryside the internet becomes more and more important. In order to offer enough access to the internet even in Ortenaukreis the village is increasing the construction of the regional broadband network. Thanks to Facebook, Skype and mail long distances can – at least virtually – be overcome.

The demographic change affects rural regions: More so in East Pommern and less so in Kinzigtal. The better off the people in those regions are the better can they face and deal with those challenges. Without work there are no prospects and there is no money. Not even in the communities. The willingness to change something is mostly up to each individual. But no matter where you meet people who are living in the countryside, they enjoy living there. They are surrounded by nature, tranquility and the place they call home in which they want to grow old.